Tag: Asian

Eleven festival

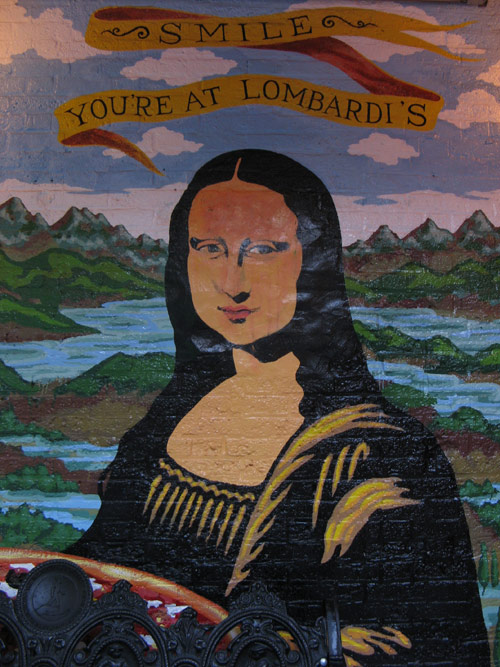

Pre-theater pizza at Lombardi’s on Spring Street with its unmissable mural of a pie-wielding “Mona Lisa,” whom manuscript experts at the University of Heidelberg have definitively identified as Florentine Lisa del Giocondo, putting all other theories to rest. (La Gioconda, inspiring artists everywhere.)

The “Pizza” episode of the History Channel’s “American Eats” series — set your TiVos for the next airing: Tuesday, April 29, 2008 — tells the story of Gennaro Lombardi, the “founding father of American pizza,” and his contribution to New York City pizza: locally grown tomatoes (instead of San Marzano), cow mozzarella (instead of water buffalo), and pies fired in coal ovens. To some extent, all the old school city pizzerias can be traced to Lombardi’s pioneering shop at 53½ Spring Street.

That first pizzeria was established in 1905, though in 1994, Lombardi’s grandson re-opened it at its current location at 32 Spring. For the pizzeria’s centennial on November 10, 2005, Lombardi’s sold whole pizza pies for 5 cents apiece.

We paid somewhat more for our pepperoni and mushroom pie, but it was still worth it.

At the Clemente Soto Vélez Cultural & Educational Center‘s Milagro Theater on Suffolk for the premiere of playwright Carla Ching’s TBA. The 1898 building is a former public school (P.S. 160), but since the mid-1990s, has served as a multicultural center for contemporary arts and art-related community services. CSV has four theaters and exhibition spaces; 53 visual artists have studios in the building.

Enhancing the LES hipster vibe was a dimly lit bar/gallery through a beaded doorway on the ground floor with vibrantly colored paintings of female nudes and cans of PBR, which we were invited to bring inside the theater.

Through April 5, theater company Second Generation celebrated its eleventh anniversary of supporting Asian American dramatic literature with ELEVEN, a month-long festival of 11 plays: one full-length production, four developmental staged-readings, and an evening of six one-acts. The centerpiece was Ching’s drama, starring Lloyd Suh, Second Generation’s artistic director and a playwright in his own right. (Both he and Ching are members of the Ma-Yi Writers’ Lab.) Suh appeared as a last-minute replacement for Ken Leung, who was called back to the set of Lost, where he has a recurring role as Miles Straume.

From TBA‘s press notes:

When Silas Park’s girlfriend leaves him, he becomes a shut-in, pumping out blistering autobiographical writings in his little East Village apartment. Just as Silas finds himself unexpectedly on the verge of literary stardom as the next Asian American wunderkind, his brother Finn shows up on his doorstep, accusing Silas of stealing his life. A play in two acts, in the crevice between fact and fiction.

An intriguing exploration of how impression and memory can form their own reality. Excellent work all around.

Oh, and we sat in front of Dr. Chen from ABC’s “Eli Stone,” whose real name is James Saito.

Yellow Face at The Public

At the Public Theater on Lafayette for a performance of David Henry Hwang’s Yellow Face, which recently extended its run until January 13, 2008. The play premiered in 2007 at the Los Angeles Music Center’s Mark Taper Forum as a co-production with East West Players.

The play, which Hwang has called a “mockumentary,” explores themes of race and art, starts off as a semi-autobiography, with a lead character named David Henry Hwang or DHH (wittily portrayed by Hoon Lee), just as he is reaching a high point in his nascent career, having just won the 1988 Tony, Drama Desk, Outer Critics, and John Gassner awards for his Broadway debut, M. Butterfly. With his new stature as the premier Asian-American playwright, Hwang was in a high profile position to lead the Actors’ Equity union protests against the yellow face casting of Caucasian actor Jonathan Pryce in the 1991 Broadway production of Miss Saigon. Hwang was initially praised by Asian groups for his support, but when Broadway producers refused to mount any Broadway run that did not include Pryce, which would result in the loss of many local jobs, the union backed down and Hwang was ultimately abandoned by the theatrical community. (Pryce, of course, went on to win both the Tony and the Drama Desk awards for his dynamic portrayal of a Eurasian pimp.)

From that point, the events turn to farce as fact blends with fiction. A stung Hwang tries to move on with his life and return to writing. Cruel irony builds when the playwright mistakenly casts a white actor named Marcus G. Dahlman (a charismatic Noah Bean) as an Asian-American in his M. Butterfly follow-up Face Value, believing the young man to be Eurasian. When Hwang discovers his error, he must go to great efforts to stretch the definition of what it means to be “Asian” – hence, a young man whose father was a Russian “Siberian” Jew, could perhaps, technically, almost be considered “Asian.” (To further bolster his position among a group of activists, Hwang produces a map showing Siberia just north of China, and a magazine cover of Buryat model Irina Pantaeva.) Dahlman, whose name is now truncated to “Marcus Gee,” goes along with the charade reluctantly at first, but eventually is so touched by how the community supports and embraces him that he comes into his own as a spokesperson for Asian-American actors, with a higher profile even than Hwang himself. Hwang manages to fire Gee – replacing him with the more traditionally Asian actor B.D. Wong — but Face Value famously flops, closing even before its Broadway premiere in 1993, ultimately losing its entire $2 million investment.

When is ethnicity “authentic”? Is identity something that can be adopted? The first half of the play was the comical high point, filled with the playwright’s self-mocking commentary and strewn with theatrical in-jokes; refreshingly, real names are used. (B.D., Jane Krakowski, then-Times theater critic Frank Rich, novelist Gish Jen and mega-producer Cameron Mackintosh are just a few who pass through the stage.)

By the second half, things take a grim and scary turn: the FBI’s investigation against Los Alamos nuclear weapons scientist Wen Ho Lee; the “Donorgate” campaign-contribution probe; the Senate investigation of the Chinese government’s transactions with Chinese-American banks, which implicated Hwang’s father Henry Y. Hwang (played with quiet dignity by Francis Jue) founder of the first Asian-American-owned federally chartered bank in the continental United States. (Although the Far East National Bank was a target of those investigations, no formal charges were ever brought against the elder Hwang, but the disillusionment of his American dream is one of the real tragedies of the play.) Things take on an even more sinister bent when a racial stereotyping New York Times reporter referred to as NWOAOC (“Name Withheld on Advice of Counsel”) tries to manipulate DHH (who once sat on the board of the FENB) into deflecting blame by betraying his father, and raising questions about whether there is any inherent paradox in the term “Chinese-American.”

In the end, there are no neat conclusions. A thought-provoking evening of theater, and a “lively, messy and provocative cultural self-portrait of a play.”

| S | M | T | W | T | F | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 |

| 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 |

| 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 |

| 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 | |||

Search

Popular Tags

Categories

Archive

- July 2010

- July 2009

- January 2009

- November 2008

- September 2008

- August 2008

- July 2008

- June 2008

- May 2008

- April 2008

- March 2008

- February 2008

- January 2008

- December 2007

- November 2007

- October 2007

- September 2007

- August 2007

- July 2007

- June 2007

- May 2007

- April 2007

- March 2007

- February 2007

- January 2007

- December 2006

- November 2006

- October 2006

- September 2006

- August 2006

- July 2006

- June 2006